Oakland

Finding My Story On Gallery Walls

by | Jan 11, 2024 10:18 am

Post a Comment | E-mail the Author

Posted to: Museum

Robin Lapid Photos

First Sundays

Oakland Museum of California

1000 Oak St.

Oakland

The Oakland Museum of California is not that crowded around noon on this Sunday. But there are a lot of families with young kids of all colors wandering around, absorbing the state’s history, taking in the stories, gazing at the pictures and artifacts.

I’m searching for my face in the museum.

Not literally, of course (though, maybe someday). But as a person of color, I often long to see a representation of myself, my identity, and my culture in the stories of others. To be seen and heard is such a wonderful relief sometimes. And as I wander through the Oakland Museum of California’s “Gallery of California History” on the museum’s first free Sunday of the month — the first of the new year — I can only hope.

It feels only natural to want my story as a Filipina American reflected in this exhibit. In elementary school in the North Bay, I’d read in school textbooks about “manifest destiny,” a belief in the god-given right of white Americans to colonize America for themselves. Granted, it was a very old textbook, but I don’t remember a lot being said about the rights and respect accorded to indigenous peoples, or to groups like the Chinese, Filipino, or Indian workers brought in to help develop the towns and communities that sprung up after the Gold Rush.

Maybe that level of inclusion is too ambitious for something as all-encompassing as the history of California. There are so many forgotten, overlooked stories to cram in. It’s reasonable to think they might not capture mine.

But there among the faces in the exhibit, I find myself.

A man and his shears.

A Filipino farmer. Not exactly my story, but a glimpse of a story I can connect with. He’d come over to the U.S. in the 19th century from the country of my parents and ancestors for the same reason they too came over a hundred years later.

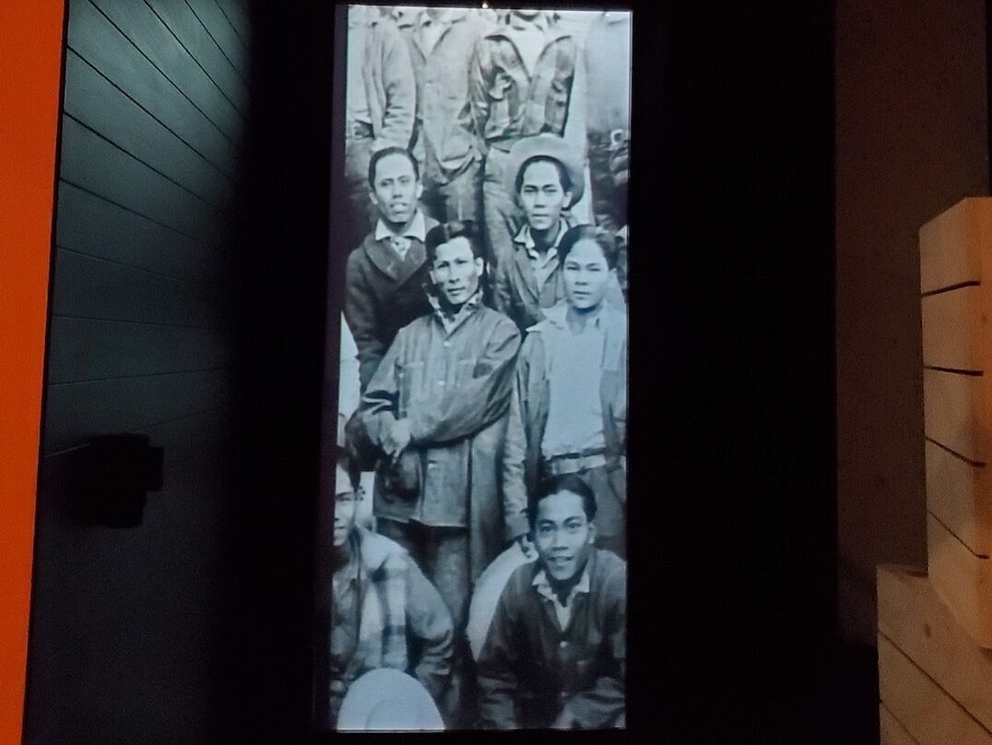

A black-and-white photo projected on a screen in an enclave of the exhibit, set up next to some makeshift fruit crates, and a giant window showing the backdrop of a sunny winter day in modern-day Oakland just behind it. Sandwiched between the snippets of stories of Chinese immigrants, Indian farmers, and Japanese settlers, the voice narration of a Filipino farmer recounting the back-breaking work, being separated to live and harvest only with other Filipinos, the racism and low wages, and his desire to stick it out, to provide for his family thousands miles away in his homeland. A familiar story from a familiar face.

I wandered through the exhibit, taking in the tales of the Japanese internment camps during World War II, the Black Power movement in the ‘60s and beyond. Baskets woven by indigenous Americans alongside photos and stories saying, “I Still Live Here.” A tiny screening room showing scenes recovered from the first Asian American film made in Oakland in 1916, a silent film written, directed, and starring Marion Wong, The Curse of Quon Gwon. An actual sign like those that still sit at the border of Oregon, Nevada, Arizona, and Mexico, saying, “Welcome to California.”

But who is welcome, and how? The question still stands today.

Welcome to California

There’s a giant map of the world at the beginning of the gallery, inviting visitors to place a sticker, a tiny red dot, on the country they came from. A father tells his kid, “Look at all the countries where these dots are — England and China and France and Japan… and a lot from the Philippines!”

I was born in Maryland, but I peel off a sticker and place it for my parents on the central Philippine island of Luzon. In a book inviting visitors to write about where they came from, I write, “My parents immigrated to the U.S. from the Philippines to find a better life.” In some ways, they found it.